The power of priorities

The idea in brief

In the battle between deliberate strategy and day-to-day priorities, even the best-laid plans can derail if employee attention is spread thin and misaligned with organisational goals. In a world of constant distractions, how can leaders ensure that what matters most gets done? The answer lies in understanding the scarcity and true value of attention—and the power of simplifying priorities to turn strategy into action.

Contents

A case study

The leadership of a large consumer bank was determined to shore up its deposit base by investing more in its relationships with its most valuable customers. Accordingly, management repeatedly communicated to employees the importance of building long-term, trust-based relationships with high-net-worth clients. They provided process scripts, digital tools, success stories on the company intranet, and consistent internal communications to reinforce this message. These efforts were supported by well-designed collateral and frequent encouragement from leadership.

However, the bank’s regulatory environment and its outdated IT infrastructure made many customer service processes cumbersome and manual. As a result, despite employees internalising the value of long-term relationships, their immediate priorities continued revolving around completing tedious, paper-bound workflows in their day-to-day efforts to maintain customer satisfaction. In practice, employees found themselves focusing not on deepening relationships but on checking off the next box in an outdated system. Objectively, from their perspective, this was the only logical answer to the question “What do I do next?”

This misalignment meant that the bank’s deliberate strategy to increase its share in the high-net-worth segment was destined to fail. Employees, constrained by real-world priorities, were unable to reorient their attention as management had envisioned. Consequently, the organisation’s actual strategy veered off-course from its deliberate one. Employees would report that they “didn’t have enough time” to focus on relationship-building.

Strategy as resource allocation

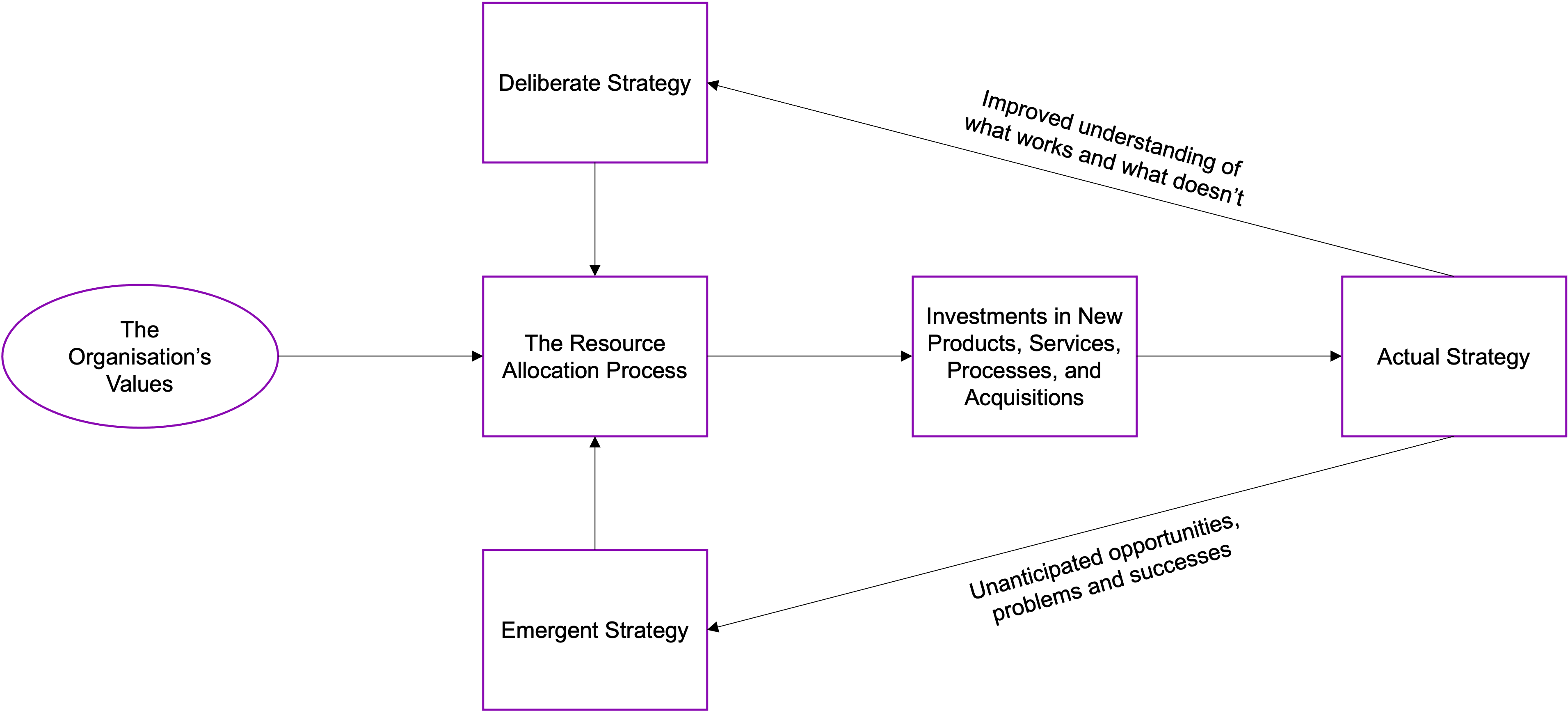

In their 2003 book the Innovator’s Solution, Clayton Christensen and Michael Raynor addressed the question of the mechanism by which actual strategy diverges from deliberate strategy under the influence of emergent strategy. They proposed a model whereby the “resource allocation mechanism” of an organisation acts as a filter on what actually happens in a firm, rather than what is intended (Exhibit 1).

In simple terms, the authors proposed that deliberate strategy, expressed through the strategic plan, interacts with the bottom-up experiences and opportunities encountered by employees day-to-day in the “fog of war”, and the organisation’s values. These three types of priorities —those set by deliberate and emergent strategy, plus the company’s values— essentially compete for resources in a diffuse, distributed and implicit day-to-day resource allocation process across the organisation that determines what actually gets done. The authors advise leaders that they can benefit from identifying the scarcest resource— capital, labour, technological advantage —in their enterprise, and understanding how it is prioritised in the day-to day, bottom-up activities of the organisations.

Exhibit 1:

The resource allocation process

Source:

Christensen and Raynor (2003)

This is a simple, compelling and intuitive model that resonates with qualitative experience of how real organisations function. It also reflects the authors’ quote of Intel’s Andy Grove:

To understand companies’ actual strategies, pay attention to what they do, rather than what they say.

However, there are some limitations to this theory. The most important one is that it is rather high-level and, therefore, difficult to apply in practice. Christensen and Raynor do not provide a particularly clear model for the centrally-important resource allocation process in their model or a clear definition of scarcity, nor do they clarify the concept of organisational values, considering it self-explanatory.

More broadly, many proponents of emergent strategy models propose that organisations end up doing a potentially unpredictable mix of what leaders want them to do and what the organisation “feels” makes sense. While uncertainty on outcomes is intrinsic to this model, a certain cloud of vagueness covers the proposed mechanism of exactly how this happens.

However, to lead organisations and drive change, we need something more concrete that can help us identify our management and change levers with some confidence.

So how does emergent strategy actually emerge? We believe that this is through the aggregation of individual prioritisation decisions on a very minute, day-to-day scale, driven by the finitude of human attention spans.

Attention is the scarce resource

Humans are really bad at multitasking. By evolutionary design, our attention span bandwidth and working memory are finite and very limited.

The bandwidth of an information channel is the rate or throughput at which it can process data. The smallest unit of volume of information is one bit, a zero or one, and bandwidth is typically measured in Megabits (millions of bits) per second, abbreviated as Mbps.

By some estimates, the totality an individual’s nervous system – the sum total of all information from all senses including sound, touch, vision, smell and taste – generates data at a bandwidth of 11Mbs. For comparison, the King James Bible is approximately 3.1 million letters in length, which can be stored in approximately 0.4 Megabytes of ASCII-encoded text. This means that our nervous system generates and then processes the equivalent of almost 3.4 copies of the Bible, a book of typically 1,000-1,500 pages in printed form, every second.

For an organism to usefully function in the real world, these data have to be filtered and sifted through to drive useful behaviours. This is what our nervous system does, with the brain playing the most important part. At the end of this filtering process, our consciousness —loosely defined here for the purposes of this post as the group of circuits in our brain that deal with reasoning and decision-making in the here and now, the part that says “I am I, I am here, and I wish to act”— has a bandwidth of about 50 bits per second. This means that our consciousness ticks along processing only one six-letter word (for example, ”coffee”) per second.

This constraint is very real and affects our lives in daily, tangible ways. For example, the limits of our attention span is why texting while driving is illegal, because the probability of an accident increases dramatically when our focus is on our phone and not the road.

We are very bad at doing well two things that require our conscious attention at the same time. Attention is the scarcest resource, constrained at every moment in time in the brains of all members of all organisations. Even in large organisations flush with cash and manpower, individual attention spans will always be very finite.

Therefore, the key question driving behaviours in real time and across a firm at every clock tick is: what do I do next?

The dynamics of prioritisation

The answer to this question lies in our model of priorities, which is central to our view of how organisations operate (Exhibit 2). We use the concept of priorities to analyse and quantify otherwise intangible elements such as corporate culture, strategy, and organisational values. We argue that this mechanism is at the heart of the resource allocation process that Christensen and Raynor describe in their work.

Exhibit 2:

The central role of priorities in organisations

Source:

Aethon

The term “priority” is often overloaded with strategic, big-picture connotations, typically evoking lists of objectives ranked by importance. For example, when asked about personal priorities, people often respond with statements like: “My children, my partner, my mental health, my job.” We tend to think of priorities as hierarchical lists of things we value most, akin to a static catalogue of ideals and goals.

Our definition of priorities here is more grounded in action and behaviour. Instead of referring to abstract values or static goals, we define priorities as the likelihood of exhibiting a specific behaviour relative to other possible ones at any given moment. In other words, we interpret priorities are inherently behavioural, observable, and measurable.

Take, for instance, a salesperson who receives an email notification from a key client. In that moment, the salesperson’s priority is to open the email—an action more likely to occur than, say, taking a coffee break or continuing to draft an internal memo. This prioritisation isn’t determined solely by the objective value of responding to the email but is also influenced by context. If the salesperson is engaged in their role, the likelihood of opening the email is high. If, on the other hand, they are frustrated and looking for another job, their inclination to prioritise this action may decrease.

This behavioural approach reveals an important distinction: the list of items we traditionally consider “priorities”—such as family, health, or career—are not true priorities in the way we define them; they are a summary of a system of values. These values form the framework within which we prioritise our behaviours, but they do not determine our immediate actions. For instance, while our children may hold the highest value in our lives, they cannot be our first priority at every moment. We still drop them off at school in the morning and then shift our attention to work, because at that moment, getting to work becomes the higher priority.

This continuous, moment-to-moment prioritisation is a fundamental behaviour of all living creatures. Simple organisms like ants or worms exhibit a narrow range of prioritised behaviours determined by basic nervous systems. For example, a soldier leafcutter ant encountering an object will prioritise examining, ignoring, or attacking it based on the context it perceives, such as the presence of pheromones or environmental cues. There is no capacity for long-term planning or complex value-based decisions—its behaviour is purely responsive.

Humans, in contrast, can weigh diverse behaviours and integrate complex values into our decision-making processes. Yet, on a day-to-day basis, even our behaviours are also constrained to a relatively predictable range of actions. Although we could theoretically jump on our desks and sing when receiving an email, we are highly unlikely to do so. Instead, we tend to choose from a handful of probable responses, informed by both context and values.

Our priority system, therefore, answers the question: “What do I do next?” It is a dynamic and adaptive mechanism that directs our limited attention to what we perceive as the most relevant behaviour at any given moment. While our actions are guided by our values, they are ultimately shaped by our immediate context and situational needs. For example, if our child wakes up with a fever, our context changes, and our priorities realign—we may choose to stay at home to care for them rather than adhering to our planned work schedule.

In essence, our priorities are not rigid, predetermined lists. They are fluid, context-dependent decisions that help us navigate the complexities of daily life, determining our actions moment-by-moment based on the question, “What do I do next?”

So how does the resource allocation process really work?

What we often refer to as “organisational priorities” are, in reality, the behaviours and goals that management wants employees to focus their attention on. However, as Andy Grove observed in the quote above, what truly matters is not what management says should happen but what employees actually do.

If attention is the scarcest resource within an organisation, management’s aim is to direct it—through communication and management channels, training programmes, and incentives—towards the activities that the deliberate strategy has identified as most value-creating. Deliberate strategy and all its associated presentations, communications and collateral acts as an input control signal, which employees must then integrate into their own personal priority maps.

It is in this process, where the intended strategy meets the reality of individual attention spans, that the friction between deliberate and emergent strategy occurs. The battle for control over an organisation’s direction is won or lost in this collision between where management wants employees to focus and where employees’ attention actually goes in order to keep the organisation functioning.

Under this light, in our opening case study on a large consumer bank, the root cause of the divergence between deliberate and emergent strategy now becomes apparent. The primary scarce resource was not capital or manpower; it was attention, misdirected away from customer engagement and towards administrative tasks. But the reality was that, while management was calling for a shift in priorities, it wasn’t providing the necessary tools or infrastructure to support this change.

In that scenario, management had three options: invest in new systems and processes to reduce the administrative burden, establish dedicated, high-touch branches that catered specifically to high-net-worth clients—creating a physical and operational space where employees could prioritise relationship-building—, or simplify its processes and document requirements, to the extent possible under regulatory requirements, to reflect the capabilities of its systems. Without such structural changes, management’s strategic ambitions were likely to remain aspirational, rather than actionable.

Simplicity rules

From this vantage point, simplicity is not just a virtue—it’s a necessity. Overwhelming employees with competing demands on their attention, without considering how these requests align with their daily realities, only serves to spread an already scarce resource even thinner.

Today, interruptions are omnipresent. Emails, instant messages, news alerts, app notifications, and social media updates constantly vie for our attention, shifting our focus in unpredictable and erratic ways. The average knowledge worker is bombarded with hundreds of these micro-distractions daily, making it increasingly difficult to maintain concentration on any single task.

This external noise is further compounded by internal demands from organisations themselves. Rather than simplifying the environment to help employees focus on what truly matters, many organisations unwittingly make the task of prioritisation even more challenging. Companies have begun to layer additional priority input signals on top of an already overwhelming base load: not just the traditional sales and profit targets, but also goals around employee development, retention, ESG targets, team-building events, and a plethora of other individually worthwhile initiatives.

The cumulative effect of these diverse inputs is fragmentation and cognitive overload. What starts as a well-meaning attempt to encourage holistic development and social responsibility ends up disorientating employees and diluting their attention across too many competing priorities. Each employee is left with the burden of resolving a more complex priority system, and their resulting range of behaviours becomes broader. As a result, coordination and consensus may become harder to establish.

This lack of clarity ultimately results in misalignment and disengagement. When employees are pulled in too many directions at once, they struggle to maintain a clear line of sight to the organisation’s strategic objectives. They may spend their days responding to a barrage of internal emails, attending meetings that feel tangential, and navigating bureaucratic workflows—all while losing sight of the fundamental goals that drive the organisation’s success.

The antidote is simplicity. Leaders must recognise that every new initiative, priority, or request has a cognitive cost. Instead of adding more layers of complexity, they should strive to reduce the noise and create clear, coherent pathways for employees to follow. This means streamlining communication channels, focusing on a few core priorities, considering not just the big picture but also the prosaic, such as employees’ actual time and motion, and ensuring that every strategic goal can actually be prioritised, not just put up on a sign in the office. By doing so, organisations can help their people allocate their attention to where it will have the greatest impact, thus converting potential distractions into focused, value-creating behaviours.

Conclusion

The success or failure of any strategy ultimately hinges on how well an organisation manages its most constrained resource: attention. Even the most well-conceived strategic plans can falter if the daily prioritisation of employee behaviours diverges from the intended direction. The real challenge for leaders is not just to craft compelling strategies, but to ensure these strategies can be prioritised into attention-driven and truly implementable behaviours across all levels of the organisation.

To achieve this alignment, leaders must focus relentlessly on simplicity. Every new priority or initiative introduces a cognitive load, clouding decision-making and diluting strategic goals. By stripping away unnecessary complexity across their operating system, and providing a coherent framework for action, organisations can channel attention towards behaviours that truly drive value. In this way, they can transform strategy from a static document into a dynamic force that guides the organisation forward—one decision at a time.

Sources and further reading

- Christensen, Clayton M., and Michael E. Raynor. The Innovator’s Solution: Creating and Sustaining Successful Growth. Boston, Mass: Harvard Business School Press, 2003.

- ‘Information Theory – Entropy, Coding, Communication | Britannica’, 30 August 2024. https://www.britannica.com/science/information-theory/Physiology.

- Miller, Earl K., and Timothy J. Buschman. ‘Working Memory Capacity: Limits on the Bandwidth of Cognition’. Daedalus 144, no. 1 (2015): 112–22.

- Leahy, Wayne, and John Sweller. ‘Cognitive Load Theory and the Effects of Transient Information on the Modality Effect’. Instructional Science 44, no. 1 (2016): 107–23.

- Rosen, Christine. ‘The Myth of Multitasking’. The New Atlantis, no. 20 (2008): 105–10.

- Parasuraman, Raja. ‘Neuroergonomics: Brain, Cognition, and Performance at Work’. Current Directions in Psychological Science 20, no. 3 (2011): 181–86.

- Cowan, Nelson. ‘The Magical Mystery Four: How Is Working Memory Capacity Limited, and Why?’ Current Directions in Psychological Science 19, no. 1 (2010): 51–57.