The Arion Imperative

The idea in brief

Despite the importance of management theories in our day-to-day lives, most of them lack of predictive value and robust empirical support. In an increasingly fast-moving and complex world, this is a serious problem that is putting organisations, their employees and customers at risk. Project Arion aims to integrate a set of leading theories about organisations across a cross-disciplinary corpus of evidence into a coherent framework to address this issue.

A crisis is brewing

Over 20 years, we have tangibly helped dozens of client organisations, private and public, overcome real problems towards value creation. We have built finance systems and organisations, developed and presented strategy papers to the Boards of publicly listed companies, and built complex valuation models to support both commercial deals and M&A negotiations.

Throughout this journey, we have found that clients are generally sceptical of consultants. We believe the skepticism is justified, because many firms, even the most prestigious and expensive ones, advertise proprietary, well-tested frameworks or management theories that are very often, in reality, hollow marketing collateral with no robust empirical evidence backing their validity.

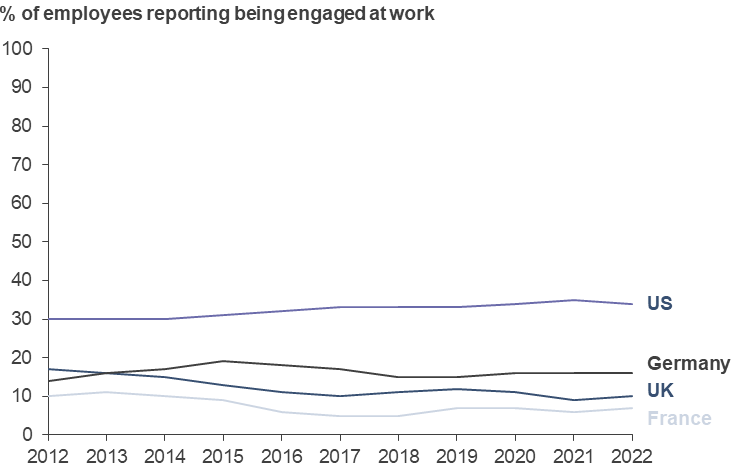

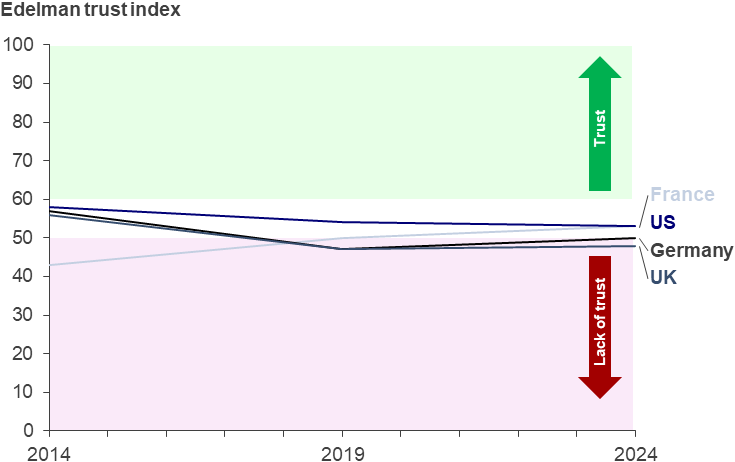

The evidence that the management theories that are championed by consultants and business schools all over the world are not fit for purpose is compelling. In key developed economies, employee engagement has been broadly flat for over 20 years (Exhibit 1). Perceptions of business as corrupt are widespread, while public trust in business remains low (Exhibit 2). Meanwhile, both anecdotal evidence and survey findings suggest that organisational change remains very difficult.

Exhibit 1:

In key developed economies, employee engagement has been low for years

Source:

Gallup; Aethon analysis

Exhibit 2:

In key developed economies, trust in business is consistently low

Source:

Edelman; Aethon analysis

As a consequence consulting firms and management theory are losing credibility. The risk is that the profession is increasingly being seen as nothing more than charlatans and faith healers.

Does theory matter, anyway?

It is, of course, a valid question whether management theory actually matters. Venture Capitalists, for example, are notoriously averse to theory-grounded thinking and can often treat it with open contempt. Similarly, many family-owned and smaller businesses simply have no time or patience for theory, viewing it as irrelevant to their problems or scale. What is the point of thinking about theory when 95% of your problems relate to the ”blocking and tackling” of day-to-day operations towards growth, product development and efficiency?

The problem with this line of thinking is that, whether you like theory or not, you always follow one, even if you don’t think you do. As John Maynard Keynes said:

“practical men who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.”

When firms began mandating a return to the office after the COVID-19 pandemic, that was based on an implied theory: that teams of people work better in-person. When deciding on annual bonuses for employees, leaders do follow a theory on what makes for good versus bad performance, and how that benefits the goals of the organisation. A choice in leadership style—whether autocratic, democratic, or laissez-faire—reflects a theory about what drives team success and morale. Every manager operates under a set of theories, explicit or not.

What does good theory look like?

There is no shortage of management theories. There are tens of thousands of books on management and leadership on sale on Amazon. LinkedIn is inundated with “thought leaders”. Everyone has an opinion on Twitter. Every high-profile CEO advertises their worldview with exceptional confidence. So how can one identify a good theory among all this noise?

The late Clay Christensen used to imprint on his students that a good theory must have predictive, not just descriptive, value. What he meant was that it should not just provide observations about the world, but offer a generalised and useful cause-and-effect model that allows managers to assess the most likely outcomes of their options.

To illustrate the point, consider Adam Smith’s concept of economies of scale. Smith noted that, if all other things remain equal, as the volume output of a company gets bigger its average costs per unit should decline as fixed costs get amortised over a larger output.

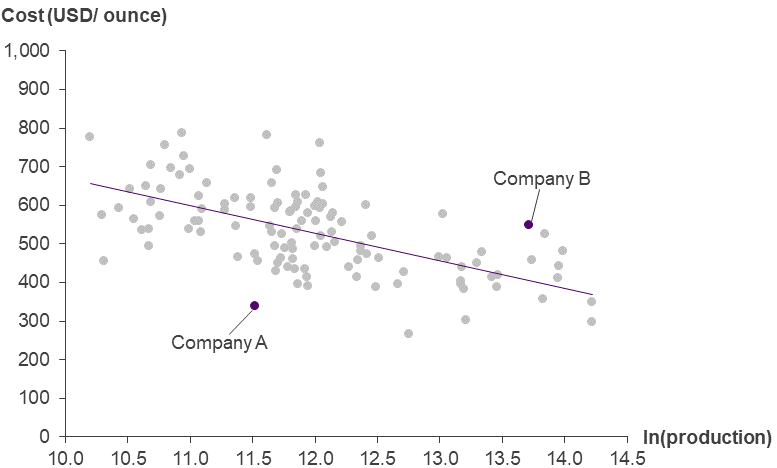

Accordingly, Exhibit 3 shows unit cost data for a group of African gold mines versus the logarithm of their output. A regression between the two variables indicates that, the idea of economies of scale holds as a general trend, with average unit costs declining as scale increases. On the basis of this finding, a descriptive managerial theory would be: “larger mines have higher operating margins. Therefore, to increase operating margins and, consequently, shareholder returns, we should scale up production”.

Exhibit 3:

Evidence of economies of scale in gold mining

Source:

African Development Bank; Aethon analysis

Is this a good theory to base management decisions on across many situations? It turns out that the predictive power of this theory leaves a lot to be desired, because Smith’s idea works when all other things are equal. In the real world, the variance of performance by company around the trendline indicates that other variables are in play.

As an example, in Exhibit 3, Company A has far lower unit costs than Company B, despite a much lower level of output. For example, increasing the scale of production in an area with labour constraints, and thus rapidly escalating operating costs, may not result in a more competitive position. Managers in the industry therefore need a more comprehensive understanding of the causal drivers of their cost drivers in order to make confident predictions.

A descriptive theory explains why things are they way they are in the present, telling us where we are and how we got here: “this is what company X did to get where it is today”. A predictive theory proposes a more generalised chain of cause and effect that helps managers reason through the possible effect of their actions in the future. A predictive theory is always descriptive. A descriptive theory is not necessarily predictive.

The importance of evidence

However, a good theory doesn’t just offer a logical and causal basis for making informed predictions. It also needs empirical evidence that supports it. Here, current management theory lacks the most.

To illustrate the problem in tangible terms, consider medicine, a profession based on well-established, empirically tested theories. In particular, consider the example of a psychiatrist and a patient, as an analogy to a consultant and their client organisation. Imagine a patient that goes to the psychiatrist and outlines a list of symptoms: they have trouble sleeping, their appetite is reduced, they feel tired all the time and have trouble concentrating at work.

The psychiatrist will then follow the clinical process of diagnosis, prognosis and treatment.

- First, the psychiatrist will perform a diagnosis, based on their many years of training, including the current level of knowledge of how the human body and brain function, as well as a diagnostic manual that has been established by their profession on the basis of clinical trials. She will ask questions, perform tests, consider co-morbidities and review the patient’s medical records. Using all this information, she will assess the patient’s cluster of symptoms to understand whether they are ill and what the illness might be. In this case, she might diagnose that the patient is suffering from depression.

- Following that, the psychiatrist will establish a prognosis, that is, an view of how the illness is likely to progress. We know that depression is not a viral infection and is not fought off by the body’s immune system. Clinical experience and trials have also shown that it is likely to persist. The clinician therefore can infer that, if the patient’s environment and lifestyle do not change, it is likely that the illness will persist and even get worse, perhaps to the point that the patient becomes unable to function in their day-to-day life.

- With this predictive theory in mind, the psychiatrist will propose a treatment plan. She might prescribe medication to support the patient, while recommending talk therapy, exercise and lifestyle changes. The prescribed medication will have been shown by clinical trials to be effective against the disease diagnosed and its symptoms at a statistically significant level, with known side effects and risks.

- Finally, as the patient continues to undergo treatment, the psychiatrist will check in with the patient to monitor them and assess whether the treatment is working and if any dangerous side effects are occurring.

Throughout this process, the clinician will be guided by the Hippocratic principle: “first do no harm”. This approach to solving clinical problems has been developed by the medical profession over centuries of work, scientific research, experiments, trials and theory-building. This toolchain allows clinical practitioners to make predictions, within an explicit, even if sometimes qualitative, degree of confidence based on proven facts on what is likely to help the patient perform better.

The problem with current management theory

It is not difficult to propose a predictive management theory that sounds good. It is much harder to prove that it works. This is especially true at the level of confidence set by the clinical randomised trial experimental method in medicine.

Clinicians deal with humans and, despite our variety as a species, we generally tend to have more commonalities than differences in our biology. Organisations, on the other hand, demonstrate far more variety, whether by industry, product focus, geography or scale. This level of variety means that they can be hard to compare like-for-like. Therefore, it is very difficult to perform randomised trials of management theories, as such experiments cannot be controlled for a limited set of variables at meaningful sample sizes.

Instead of randomised trials, business schools and consultants rely on case studies to illustrate their theories and demonstrate that they work. While helpful, the inherent diversity in organisations means that the study of an individual situation in a specific company can hardly provide compelling evidence that a theory will works even in a situation organisation in another company.

Finally, many management frameworks are disjointed: for example, there are numerous corporate strategy, change management, organisational behaviour and customer value frameworks. MBAs and management consultants are trained on this disparate set of tools, often proprietary to their firm – cost analysis, value driver trees, 2×2 portfolio theory matrices, customer loyalty measurement tools. Most firms lack a robust, integrated, data-supported and consistently deployed way of thinking about all of these topics together at the organisational system level in a coherent whole. Continuing from the analogy to clinicians, it’s like teaching trainee doctors how to test patients and prescribe medication without a theory on how the human body works.

Organisations thus have to rely on the ability of individual managers to identify patterns in their day-to-day experiences at work and establish the applicability of each framework they have learned in their career in situational contexts. The onus often falls on managers with very little guidance.

Our proposal

This post up to now may appear like a polemic. It is not our intent to throw mud on the whole construct of modern management theory. What we propose is that, as a starting point, managers should be aware of three things when making decisions, namely that:

- Whether they reject formal theory or not, they are using theory

- They should always interrogate their theory on a predictive, not just descriptive, basis

- They should look for objective, empirical evidence that the theory works

All managerial decisions that create value are made under uncertainty. Clairvoyance does not exist. We cannot hope to make perfect decisions, but it is our responsibility to make well-informed ones, or we create risks for our organisation, its customers and employees. Since all decisions are made on the basis of some theory, we need to be cautious that we are employing a good one, especially when the stakes are high.

Project Arion aims to help address this issue. Our goal has been to distil essential principles from a range of subjects into an evidence-based, integrated and practical framework for understanding organisations and their behaviour, to be able to support change efforts on the basis of robust, empirically-validated theory. We are trying to synthesise and communicate what is best of breed today, not re-invent the wheel, to help managers build better organisations.

Sources

- ‘Global Indicator: Employee Engagement – Gallup’. Accessed 7 May 2024. https://www.gallup.com/394373/indicator-employee-engagement.aspx.

- ‘2014 Edelman Trust Barometer | Edelman’. Accessed 14 May 2024. https://www.edelman.com/trust/2014-trust-barometer.

- ‘2019 Edelman Trust Barometer | Edelman’. Accessed 14 May 2024. https://www.edelman.com/trust/2019-trust-barometer.

- ‘2024 Edelman Trust Barometer | Edelman’. Accessed 14 May 2024. https://www.edelman.com/trust/2024/trust-barometer.

- ‘Working Paper 222 – Economies of Scale in Gold Mining | Banque Africaine de Développement’. Accessed 27 May 2024. https://www.afdb.org/fr/documents/document/working-paper-222-economies-of-scale-in-gold-mining-52529.

- Moore, Frederick T. ‘Economies of Scale: Some Statistical Evidence’. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 73, no. 2 (1959): 232–45. https://doi.org/10.2307/1883722.