People, technology, and change

The idea in brief

Technological change is about navigating the entanglement between people and their tools. As companies evolve, it becomes harder to efficiently align technology with the group’s priorities. Organisations can manage this “technology treadmill” more effectively by continuously studying whether their processes make day-to-day, rather than high-level, sense in their employees’ working lives.

Contents

The technology treadmill

How many companies can you think of where the salesforce sings the praises of the Customer Relationship Management (CRM) system? Or where the Finance department does not have to arduously compose potentially haphazard reports in Excel, circumventing the Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) system, because of its limitations?

Most leading organisations are running on a constant technology treadmill. As market conditions change and strategies evolve, teams continuously adapt and do what makes sense towards executing their job. Without steady investment in new products, processes and tools, existing systems gradually fall out of sync with the requirements of the organisation. Employees look for time-consuming workarounds like manual reports or ad-hoc manufacturing processes.

To address such issues in organisations with significant technical debt, leadership teams often decide to embark on technology transformation projects—deliberate and coordinated efforts with specified timelines, often in “waves” of execution, aiming to step up the company’s systems and technology.

Nevertheless, the consensus estimate —albeit a tenuous one, in terms of empirical evidence— is that 70% of such efforts fail to achieve their target impact. In response to this perceived failure rate, each consulting firm has its own view on the right approach for de-risking such projects. However, these theories are often borne out of qualitative experience, not grounded on a solid framework backed by empirical evidence. It is also notable that many among the world’s large consultancies are involved in the design and implementation of such transformation programmes.

Why is it that, despite all the innovation taking place in the fields of technology and software development, deployment and infrastructure, change in large organisations remains so difficult? We believe that this is because, very often, this change is pushed top-down from a strategic plan, with limited understanding of how organisations become entangled with their technologies in shaping their priorities (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1:

In organisations, people and physical assets are entangled

Source:

Aethon, Shutterstock

It might sound prosaic, but leaders deep in the strategic planning process often forget that people embrace technologies that make sense. Without congruence between the new systems and the employees’ priority matrix, their cognitive map of what matters for the business, this will not happen.

Our view is that too often leaders pursue technological change without thorough consideration of how the target day to day priorities of employees need to change. This requires thoughtful analysis of what employees should be doing with their time and why they should be using the new system, how this relates to the strategic plan, and whether the user requirements defined make sense not just in a broad, top-down strategic terms but also in a day-to-day, time and motion ones.

To establish a theory of the relationship between an organisation’s priorities and its technology, it might be helpful to consider a case study on the relationship between groups of people and things in a technologically much simpler time, without cloud-based microservices, automated production lines and ERPs, in a time where the pace of technological change and its impact on organisations were so slow that it can be observed in the archeological record.

A unique society

In 1958, the controversial British archeologist James Mellaart began excavations at Catalhöyük and discovered the ruins of a settlement like no other (Exhibit 2).

Estimated to be densely populated by between 3,500 to 8,000 people in an area of 13.5 hectares (135,000 square metres), Catalhöyük is both very old and large for its time. It was occupied between the Neolithic in 7,100BC for 1,500 years to the Chalcolithic in 5,600BC and is among the earliest human settlements ever discovered. It is also among the largest settlements of that era of human pre-history. In very simple terms, Çatalhöyük offers us a glance at a time and place where humans were inventing farming and villages, and figuring out how to live together and permanently in big groups, in one place.

There are many things that make Çatalhöyük a mind-blowing case study in human organisation: the fact that there were no streets, with people moving from house to house on the rooftops; the lack of strong evidence of a social hierarchy and prominent buildings with a central function, suggesting more of an anarcho-communist society than the hierarchical kingdoms that developed later in Egypt and Mesopotamia; the underfloor burials in the same house of people who do not seem to be genetically related to each other but likely feasted together.

Exhibit 2:

The Catalhöyük excavation site and reconstruction

Source:

Shutterstock

In simple terms again, one of the very first villages we know of looks nothing like the villages we recognise today. It paints a picture of a very strange place to live in, by our modern standards; yet was stable enough a society to survive for 1,500 years – about 60 generations.

Villages, towns and cities are technological inventions, systems of buildings that allow us to live densely together. How did this unique configuration of technology and people come about, and why?

A technological yoke?

Among all these peculiarities, there is another important finding at Çatalhöyük that is key to answering these questions: as the site’s archeology evidences the transition from hunter-gathering to settled village life, it offers us a glimpse of the development of this technology over a period of centuries, and its implications on the society. On that topic, the findings would be surprising to most people

Forensic archeology on the remains found at the site shows that as the diet and economy of the inhabitants changed from nomadic to settled life, they seem to have been physically worse off. The technological transition to agriculture was, literally, painful. The average height of individuals is lower, evidence of malnutrition is more frequent, their bones have more signs of injury and damage from years of hard manual labour, and disease in the dense and unhygienic settlement seems to have been more frequent. On all of these well-being metrics, the life of a villager seems to have been harsher than that of a nomadic hunter-gatherer. This is a finding that is also corroborated with other sites where similar transitions were observed.

We tend to be captive to an underlying view of progress where technological breakthroughs are bright sparks of genius and are adopted because they improve well-being. The bright spark lights a figurative fire, and then the lines on two charts rise together as the technology spreads: the economic output of the population and individual happiness rise together. Like a game of Civilisation, new technologies are the key to progress and the improvement of our lives; all lines go up.

Yet, at Çatalhöyük, not all lines go up with the gradual adoption of the technology of the built settlement. So, if the life of an early farmer was worse than that of a hunter-gatherer, why did the inhabitants of Çatalhöyük ever make this transition?

The concept of entaglement

Humans build things, and then these things change us. This is a phenomenon that the archeologist Ian Hodder, who leads the Çatalhöyük Research Project, has called entanglement: the idea that human groups and their material culture shape each other in both directions. This gradual process of entanglement between people and things can eventually lead to entrapment.

The basic pillars of Hodder’s theory could arguably be simplified as follows:

- Individuals do what makes sense: individual people adopt, build and invent technologies in incremental steps that make sense on their own.

- The group adapts: our organisations slowly reconfigure themselves to couple with the technology through individual-level changes in priorities.

- Individuals forget: the organisations eventually become dependent on the technology to function, even if sometimes the new configuration is suboptimal for the individual. The why we do things the way we do is lost in the hustle of trying to do the things we do.

At its core it is an intuitively sensible idea: that new technologies are not adopted in a bright spark of excitement because they make everything better, but in incremental steps. Each step makes sense on its own but cumulatively they may lead to inefficiency and sub-optimal outcomes. This is as true now as it was then, albeit at a faster overall speed. Our technology and culture may have evolved since Çatalhöyük, but we are still the same creature.

Humans continue to adopt and do technologies when they make sense and get things done in their immediate, practical, day-to-day context.

People do what makes sense

We know from Göbekli Tepe, an older site in Turkey, that the idea of a stationary built environment preceded Çatalhöyük. This means that the idea of “village” was there before the idea of ”farm”. There just wasn’t a reason for a village. Hunter-gatherers, like the Native Americans in colonial times who followed the buffalo herds, are nomadic for a reason: they need to be able to follow their source of food.

Humans likely started on the path to agriculture by planting a few seeds in an area where they expected to return to in the summer, probably as a way to diversify, not replace, their food supply. That made sense, so they did it and it worked, so they continued doing it. Over time, they figured out ways to improve the process and get better yields. This also made sense, so they did that too, and continued to experiment. At some point, they had good enough results to get the confidence that it was worth putting in the hard labour of working a larger area of land.

This behaviour also materialises today, in modern organisations. People still tend to do and tinker on improvements on what makes sense. Conversely, they will abandon technologies that do not. For example, to the dismay of sales managers bemoaning the poor quality of the data in their Customer Relationship System (CRM) in many organisations, salespeople will end up not maintaining their data on such systems if they do not add value to their efforts of generating and pursuing leads.

The group adapts

Humans did not just discover agriculture one day and simply pivot their hunter-gatherer way of life the next. The process was incremental, slow and full of experimentation over many generations. It also resulted in changes to the way they organised themselves geographically, relationship-wise and, ultimately, in what they measured as valuable. We observe that as a change in the culture, which is the observed outcome of group adaptation.

Geographically, the gradual transition to agriculture also meant that nomadic life was increasingly constrained in an ever-shrinking radius around crops until, finally, the group had to stay put on a permanent basis. The more work humans put into their crops, the less likely they were to leave them to the whims of the elements or the appetite of wild animals or other tribes. It is therefore speculated that the strange architecture of Çatalhöyük has a defensive aspect, with the rooftop-based town being a proto-fort.

Concurrently, the group adapted in how it was internally “wired” through social relationships: more intensive agriculture needed larger family units, that would have been less sustainable under a nomadic lifestyle. Cross-collaboration between households led to a change in family priorities, behaviours and customs. Community life and religion gradually organised itself a lot more around the cycle of the seasons and the harvest rather than the hunt. Evolved customs that supported a larger but well-bonded community such as feasts and festivals were more useful towards the success of the group. Ultimately, the groups that went through technological transition and succeeded, like Çatalhöyük, adapted their priorities and behaviours at the individual level to emerge changed.

Individuals forget

Over time, the abnormal sometimes becomes normal, as is said.

In the broader Christian world, the majority of households decorate Christmas trees during the winter festivities. When doing this, most people do not pause to think about the meaning of the custom, which makes no sense in the Christian context. There is no mention of a Christmas tree in the nativity story. The custom is likely to have pagan origins and to have originated in Germany but, despite numerous theories, its original meaning is lost to time.

Nevertheless, the custom of Christmas trees persists because parents love their children, children love the Christmas presents that the tree shelters, and toy companies like the profits that come from the holiday sales. In the context of the group, the custom still makes sense, even though its original meaning is forgotten.

In the case of Çatalhöyük, sixty generations —our estimated lifespan of the settlement— is a long time. It is very likely that the customs of hunter-gatherers formed the cultural bedrock that early society was built on, but that culture evolved. Evidence suggests that hunting, from the primary source of food and its associated religious ritual centricity, likely became a custom associated with male prestige but prowess. It is also very likely, given their, evidently, oral culture, that they did not recall that this was their ancestors sole source of food.

Therefore, with the passage of time, the people of Çatalhöyük continued the ways of their forefathers, but adapted to their settled life. In the process, they had forgotten their peoples’ original way of life and the reason hunting initially mattered for. Furthermore, lacking any reference, they were very likely oblivious to their higher disease rates and lower quality of nutrition compared to their hunter-gatherer ancestors.

In larger scale societies, this process may take generations. But in modern organisations, which hire new people and experience turnover, it can be relatively fast. Many times, a new joiner is inducted and trained on processes centred on technologies deeply embedded in the company’s operating system. They end up following them because they are necessary to the business, but with no understanding of why or how they came about and whether they are still optimal.

A company of 2,000 people, 400 of whom do sales, may still utilise a complex sales process based on Excel spreadsheets with Visual Basic macros instead of a modern CRM. With scale and turnover, that institutional memory of specific technology and process choices is often lost, with processes, potentially painfully inefficient ones at that, crystallised around them and shaping daily priorities and emergent strategy. The real reason for the initial choice of solution may have been its low cost, which suited the priorities of a startup. Entangled with it and reliant on its data now, the organisation is captive to the spreadsheet.

Implications for managers

We believe that the idea of entanglement is very relevant to modern management and has a lot to offer to organisations that embark on technological change programmes. If leaders appreciate that their teams are entangled with their technology, they can consider the process by which it happens—individuals do what makes sense, groups adapt and individuals forget—they can ask the right questions throughout a transformation journey or at all times on the technology treadmill.

These projects typically have a well-defined playbook in four parts, namely:

- Establish the point of departure

- Establish the point of arrival

- Develop a roadmap

- Execute the implementation:

Managers who understand the phenomenon of entanglement should incorporate a set of key questions across all four steps of this journey.

Establish the point of departure

At the beginning of any ambitious large scale technology programme, organisations begin by assessing what the current key technological pain points are and how they impact performance.

This step is often performed at a high level because the operating assumption is that employees and leaders are quite aware of the issues. Top-down benchmarking of e.g. cost structures as margins is therefore typically combined with team interviews that generate lists of issue that are tied together in a driver tree.

The concept of entanglement introduces a bit more organisational soul-searching at this stage. The key question to ask at each interview is: how did we get here? Plumbing the organisational memory can help understand what made sense during the journey that brought us to our current point of departure, and the findings can help inform the next step.

Establish the point of arrival

At the next step, transformation teams typically develop a top-down view on what the required technology features need to be for the strategic plan to be successful. The driver tree established during the first step is worked top-down to identify the target performance KPIs needed to achieve the financial targets in the business plan. The team then validates its high-level technology and architectural choices based on the metrics targeted. What processes and systems will we need to achieve the targets, and what is the required investment?

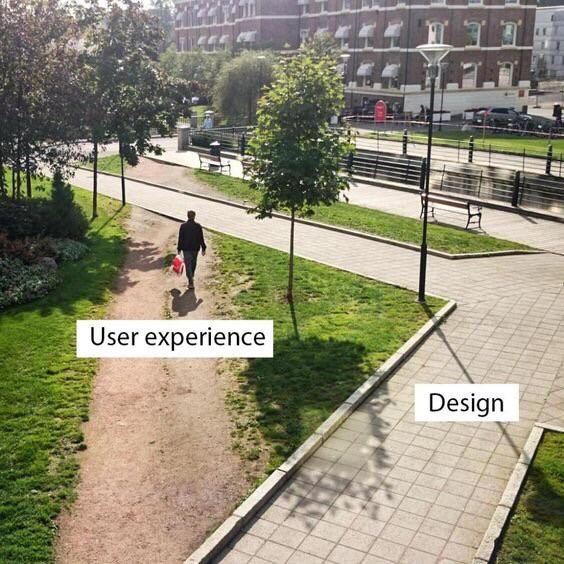

This is often the step of the journey where the most expensive mistakes are made. Our proposal is that teams should invest time to reflect upon their findings to assess and interview teams on whether the target operating model will make day-to-day sense to them. Often, solutions designed on paper look good in theory but not in day-to-day practice (Exhibit 3). Despite the pressure to deliver the financial targets, the stakes are high when drawing the high-level blueprint of the point of arrival as many key, axiomatic architectural decisions are set in stone here. It is important, above all, to be practical.

At the same time, it is also important to workshop an additional key question: assuming we deliver what makes sense, how will the group change? Just like in Çatalhöyük the technology of the village changed the culture, so do modern technologies affect the interactions and culture of organisations.

Develop a roadmap

With a clear view of where the organisation needs to get to, transformation leaders typically then turn to the journey there. The next step is, therefore, to design establish a transformation programme plan with specific milestones, budget, accountability matrix and governance structure to get to the point of arrival. This ultimately takes the form of a programme workplan.

As entanglement is a gradual process, it makes sense that an approach that recognises it should rely more on agile, rather than waterfall, project delivery across the design, development, testing and rollout stages of the programme. The big advantage of agile is its ability to deliver change in smaller, incremental deliverables, allowing for the organisation to gradually disentangle itself from its existing technology stack and entangle with the new one. The approach also allows careful monitoring of the culture and other impacts that the new technologies have along the way.

The organisation can thus pursue a ”glide path” to its target state, where the technology stack better reflects the intended priorities and vice versa.

Execute the implementation

This is where 80% of the work is. Over a potentially long period of time, the transformation team will embark on the initiatives outlined in the previous step with regular programme office meetings, issue resolution and escalation, and change management.

There are many solid frameworks for approaching the management of complex transformation projects, along with software tools to support governance workflows. Concurrently, many consultants will stress the importance of momentum and the decision drumbeat—a sufficiently disciplined organisational mechanism for resolving bottlenecks that might appear during the project, like a particular solution taking longer than anticipated to deliver.

A recognition of the effect of entanglement requires that the Programme Office always remains vigilant on whether the new technology still makes sense, and, if not, why and how any issues can be mitigated. Again, an agile delivery approach, rather than a “big bang” waterfall model, can help catch issues early on, derisking the process.

Conclusion

Organisations embarking on technology transformations must recognise that entanglement with existing systems runs deep, shaping their priorities in a back-and-forth interaction between people and things. Leaders who truly understand this interdependency are better positioned to guide their teams through change.

A thoughtful transformation requires more than just a top-down strategic plan; it demands a deep understanding of how employees’ day-to-day priorities align with the new systems and how those systems will impact the organisation’s culture and workflow.

By integrating the concept of entanglement into their transformation approach, leaders can anticipate challenges and design solutions that not only make sense on paper but also resonate with the realities of their teams. Through continuous reflection and a willingness to adapt incrementally, businesses can evolve with their technology, achieving meaningful change while avoiding the pitfalls of becoming trapped by their own innovations.

This mindset, rooted in both historical and modern contexts, is essential for navigating the complexities of the ever-changing technological landscape.

Sources and further reading

- Noria, Nitin, and Michael Beer. ‘Cracking the Code of Change’. Harvard Business Review, https://hbr.org/cracking-the-code-of-change 2000.

- Hodder, Ian. Studies in Human-Thing Entanglement. 1 online resource (171 pages) : illustrations (some color) vols. [Stanford, California]: [Ian Hodder], 2016. http://www.ian-hodder.com/books/studies-human-thing-entanglement.

- Ian Hodder | What We Learned from 25 Years of Research at Catalhoyuk. The Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, n.d. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o70A1VqrxEQ.

- The Oxford Review – OR Briefings. ‘Do 70% of Organizational Change Projects Really Fail?’ Accessed 16 September 2024. https://oxford-review.com/do-70-of-organizational-change-projects-really-fail-video/.

- ‘The Science behind Successful Organizational Transformations | McKinsey’. Accessed 17 September 2024. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/successful-transformations.

- ‘Christmas Tree | Tradition, History, Decorations, Symbolism, & Facts | Britannica’. Accessed 12 September 2024. https://www.britannica.com/plant/Christmas-tree.