Emergence and organisations

The idea in brief

Examples from nature suggest that human organisations exhibit emergent behaviour, where collective dynamics self-regulate beyond individual control. Through this lens, leadership should be viewed as a two-way conversation with the organisational 'hive mind', rather than top-down command-and-control. Leaders must recognise that as organisations scale, their ability to fully direct outcomes diminishes, requiring a more adaptive and tailored approach.

Contents

Consider the ant

Ants are arguably one of the most successful family of species on Earth. In fact, by many metrics they are more successful than humans. Their global population is conservatively estimated at 20 quadrillion individuals, whose combined biomass is estimated to exceed that of all wild birds and mammals and makes up about two thirds of that of all insects. Well before humans spread all over the Earth, the ancestors of ants had adapted to the conditions of every continent, with the exception of Antarctica.

The success of ants lies in their eusociality. All ant species are eusocial, which means that they are organised in colonies of overlapping generations that collectively care for their young. Eusocial species populations also have strict division of labour, with each individual belonging to a caste that is morphologically specialised for a defined type of work. Bees, a fellow member of the hymenoptera order of species, are also very famous for their eusociality. However, not all species of bees are eusocial, whereas all species of ants are eusocial.

The miracle of eusocial species is that these colonies, that can number thousands or even millions of individuals, are self-organising. There are no ant bosses or managers, and queens do not issue instructions to workers. The royal title itself is an 18th century misnomer, as this caste has no direct control over the actions of other ants; Queens are just egg-laying machines, not rulers of the colony. There is no chain of command and no pecking order of alphas or betas. Individual ants perform their narrow range of specialised tasks in their caste, assess their environmental context based on their sensory organs, and communicate with each other through pheromones. Organisation emerges through these relatively simple sets of interactions. Colonies are constructed gradually, in the context of their environment and, if successful, function like clockwork, even though nobody is in charge. When a leafcutter ant colony decides to move when its nest floods, no individual ant makes a decision; the colony system ”decides” to move.

Exhibit 1:

Ant colony emergence

Source:

TED

Thus, ants, as the extreme of sociality in nature, are an incredibly interesting case study of organisation. Individual ants are almost irrelevant, in that the vast majority of them cannot even reproduce, let alone survive on their own, but ant colonies tend to dominate their environment, pushing solitary insects to the edges of their territory and specific, narrower niches. Eusocial animals compete in their habitat primarily at the population level.

The concept of emergence

Ants can be viewed as cellular automata, a mathematical abstraction of a system composed of a population of small, simple machines that interact with each other. Such systems can self-organise without supervision or external instructions, and demonstrate order and patterns, effectively assembling into a larger machine without a blueprint or designer. Cellular automata have been used to explain a broad range of phenomena including pattern formation on mollusc shells, the formation of snowflakes and the intake and loss of gasses by plants.

Such systems have been amply shown to demonstrate a phenomenon called emergence. Although the term was first used in 1875 by the philosopher George Henry Lewes, the idea has existed since the time of Aristotle, whose exploration of the concept is the common expression “the sum is different than the parts”. In emergent systems, something new, that demonstrates what we humans recognise as order, appears from the self-regulating interactions of simple, smaller functional units that are not regulated by any overarching “managerial”, order-giving mechanism.

Emergence is a much more common phenomenon in nature than its complex-sounding definition suggests. Lewes gave the example of water molecules, which have different properties to either the oxygen or hydrogen atoms that compose them, as an illustration of emergence resulting from two things forming a new thing by interacting. More visually, the behaviour of a white blood cell pursuing a bacterium, as shown in the video in Exhibit 2, is a striking example. There is no intelligence, nervous system or conscious drive in this single cell, and none of the individual complex chemical compounds composing it through an unimaginably sophisticated nexus of chemical relationships are imbued with a sense of purpose towards pursuing its target. Yet, overall, as a system, the odd, mindless blob that this cell is performs a determined, focused task with admirable precision. The cell is thus, indeed, a sum that is different than its parts.

Exhibit 2:

Neutrophil white blood cell pursuing bacterium

Source:

Vanderbilt University

The whole phenomenon of life itself can be viewed as a “ladder” of emergence. Chemical compounds make cells and specialised cells assemble into organs that are parts of organisms. Being organisms ourselves, we, as conscious human beings, instinctively put our experience of the world in its centre and tend to consider this the final step of the ladder. Eusocial animals, like ants, show that this perspective may be incomplete without understanding the behaviour of groups.

Emergence in populations

Due to their extreme social traits, ants demonstrate clearly yet another level of organisation and level of analysis in this ladder above that of the organism, sometimes called a superorganism: a system of organisms that demonstrates emergent properties that its individuals do not have. The superorganism demonstrates all key criteria of common definitions of life: homeostasis, organisation, metabolism, growth, adaptation, response to stimuli and reproduction. Like organisms, ant colonies are born, grow, reproduce, feed and, in emergencies, can even move as a discernible, physically united being. Philosophers, scientists and artists from the time of Aristotle, who declared bees to be, like humans, “political animals”, have taken note of the existence of this additional rung of in the ladder of emergence, which is so evident in the presence of eusociality.

What happens if we, like Aristotle, take a bird’s eye view of a business and view it with the same eyes that we look at an ant colony?

Through this, somewhat discomforting, lens, we could ask many questions, the answers to which could be consequential in how we think about organisations and management theory. For example, why do we need a managerial class in our organisations, when ants do not? Is there really value to the relatively abstract concept of leadership, and, if so, through what mechanism? And can human organisations be viewed as literal living creatures, with parallels to the eusocial superorganism?

Implications for organisations

All this may appear, at best, academically interesting but irrelevant to managers on their day-to-day work. Who cares about ants when you are trying to put together a business case proposal for entry into the Indonesian market for the Board?

However, the question as to whether an organisation has emergent, superorganism-like behaviour, is of paramount importance to how we should approach management. If it is indeed true that systems of people are something different to their parts and that they demonstrate their own “will”, in the sense that the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer defined it, then this suggests that, for example and at a certain scale:

- There are limits to management agency and authority, even in the C-suite

- Organisations demonstrate homeostatic behaviour that actively resist change at the system, not individual employee, level

- Organisations may not even be controllable, even though we, in our individual human minds and perspectives, may maintain an illusion that we control them

Therefore, no matter how compelling the business case for entry into the Indonesian market might be in one’s presentation and spreadsheets and how well it is articulated in the boardroom, the organisation may, as a system, push back on it – regardless of what you or even the Board may think.

Emergent strategy

Turns out that this line of investigation has indeed been explored in management theory. There were threads of research on this topic in the 1960ies, under the field of cybernetics, but did not really yield anything noteworthy. Nevertheless, managers, consultants and businesses academics remained painfully aware of the fact that change efforts and explicit, top-down strategies largely fail. Therefore, questions persisted about why that is the case.

Some insights around this phenomenon began emerging more prominently in the literature of the 1990s, with the rise in the economic and media importance of highly valuable, VC-funded, innovative tech companies. These new stars were relying on more agile and incremental approaches to strategy and growth than the conglomerates that were fawned upon in the 1980ies. They were the the pioneers in the development and adoption of now-widespread business concepts like pivoting, product-market fit and agile delivery, among others.

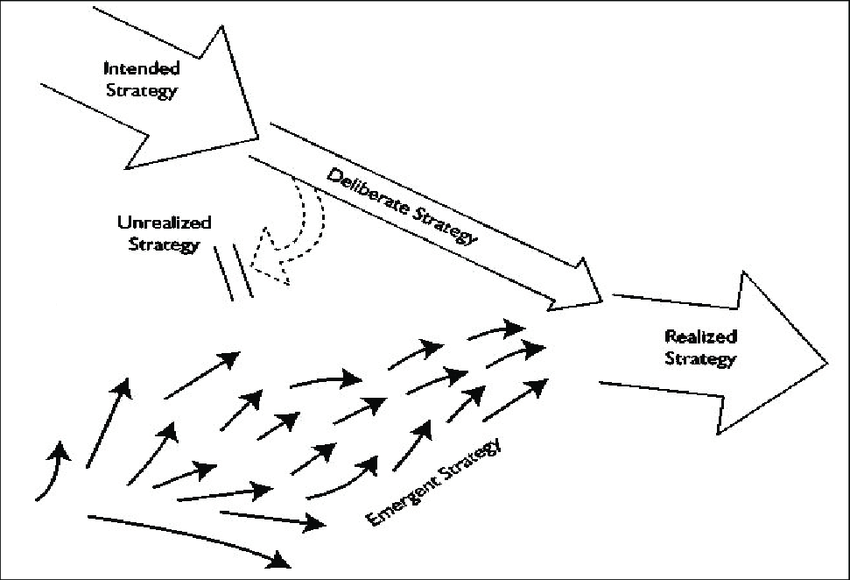

At the early stages in that wave of thinking, Henry Mintzberg coined the term emergent strategy to describe the influence of the many, discrete and incremental actions and decisions of the organisation on an organisation’s actions, versus a firm’s top-down, deliberate, strategy (Exhibit 3). In his book The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning (1993), he described the process of emergent strategy formation as follows:

“Actions were taken one by one, which courage in time in some sort of consistency or pattern. For example, rather than pushing a strategy (real plan) of diversification a company simply makes diversification decisions one by one, in effect testing the market. First it buys an urban hotel, next a restaurant, and then another of these, until a strategy (pattern) of diversifying into urban hotels and restaurants finally emerges.”

Exhibit 3:

Emergent versus deliberate strategy

Source:

Mintzberg (1994)

In other words, Mintzberg highlights how strategy, as a pattern or position (e.g. differentiation versus low cost) often is an a posteriori result of the organisation’s performed actions and not an a priori plan. Just like an ant colony gradually takes root and develops incrementally, the organisation acts over time in discrete and individually sensible steps. In hindsight and given evidence of success, management explains, identifies the pattern that has been followed and delivered results, and ”leans into” it. In his own words, emergent strategy forms, whereas deliberate strategy is formulated, and the two modes of strategy formation are in constant interplay.

The use of the concept of emergence in business is therefore neither fringe nor inapplicable. It has, in fact, been observed and articulated before by notable business thinkers. The natural next questions are: what are the mechanisms through which it occurs, how do we recognise when it has, and what are the implications for managers?

Our view

We believe that there is a large basis of evidence, both empirical and theoretical, that supports the view emergence in large scale organisations is real, even taking it to the extreme of stating that a figurative organisational “hive mind” exists past a certain scale.

What is even more important, are the avenues of thinking about organisations that this way of looking at them opens up. Humans, with their complex behaviours, use of language and reasoning are not as simple cellular automata as ants, but the idea of cellular automata can provide a grounding for thinking about organisations, their strategy and their ability to accept change top-down, in terms of that framework.

The key implication is that only a small subset of the actual activity of management is top-down command-and-control. Most is, or should be, a “conversation” with the “hive mind”. If organisations are indeed complex systems, then a systems way of thinking can provide us with a language and approach for assessing whether there are indeed patterns to their behaviour, as is the claim of all management theory and, more so, what the exact mechanisms are that drive these patterns.

We’re convinced that emergence in large-scale organisations is not just a theory but a reality—one that suggests a “hive mind” does indeed form at scale. This perspective transforms how we approach strategy, change, and management itself. Viewing organisations as complex, adaptive systems allows us to decode the deeper patterns driving their behaviour. By embracing this systems thinking approach, we unlock new tools for navigating strategy, change, and innovation. This is the foundation of our management framework, and we continue to refine and share these insights as they develop.

Sources and further reading

- Christensen, Clayton M., and Michael E. Raynor. The Innovator’s Solution: Creating and Sustaining Successful Growth. Boston, Mass: Harvard Business School Press, 2003.

- Mintzberg, Henry. The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning. Harlow: Pearson, 2000.

- Kozlowski, Steve W. J., and Georgia T. Chao. ‘The Dynamics of Emergence: Cognition and Cohesion in Work Teams’. Managerial and Decision Economics 33, no. 5/6 (2012): 335–54.

- Schultheiss, Patrick, Sabine S. Nooten, Runxi Wang, Mark K. L. Wong, François Brassard, and Benoit Guénard. ‘The Abundance, Biomass, and Distribution of Ants on Earth’. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119, no. 40 (4 October 2022): e2201550119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2201550119.

- Ward, Philip S. ‘The Phylogeny and Evolution of Ants’. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 45 (2014): 23–43.

- Hölldobler, Bert, and Edward O. Wilson. The Superorganism: The Beauty, Elegance, and Strangeness of Insect Societies. 1st ed. New York: W.W. Norton, 2009.

- ‘Aristotle, Metaphysics, Book 8, Section 1045a’. Accessed 21 June 2024. https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0051%3Abook%3D8%3Asection%3D1045a.

- Abbate, Cheryl E. ‘“Higher” and “Lower” Political Animals: A Critical Analysis of Aristotle’s Account of the Political Animal’. Journal of Animal Ethics 6, no. 1 (1 April 2016): 54–66. https://doi.org/10.5406/janimalethics.6.1.0054.

- Hofstadter, Douglas R. Godel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1993.